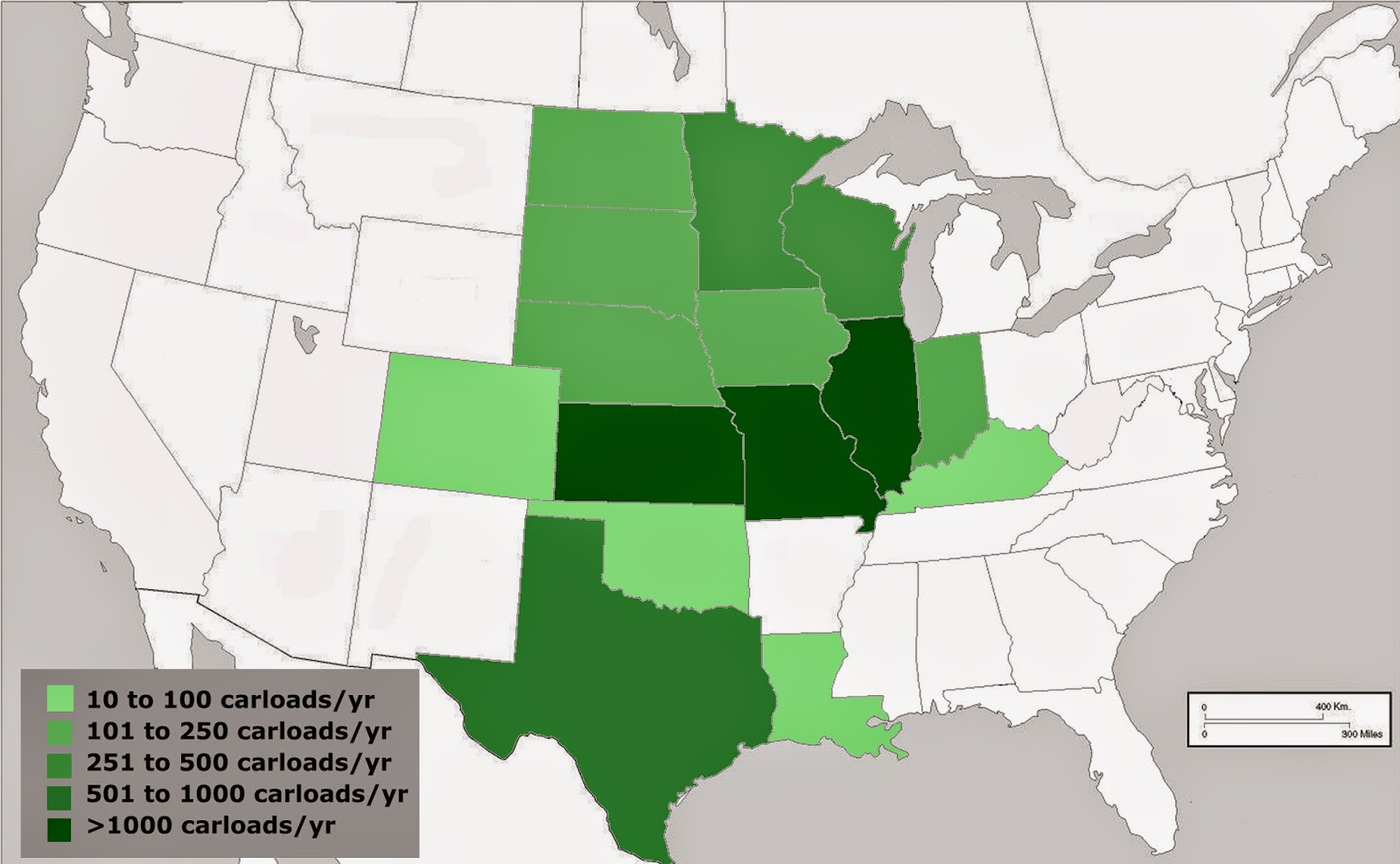

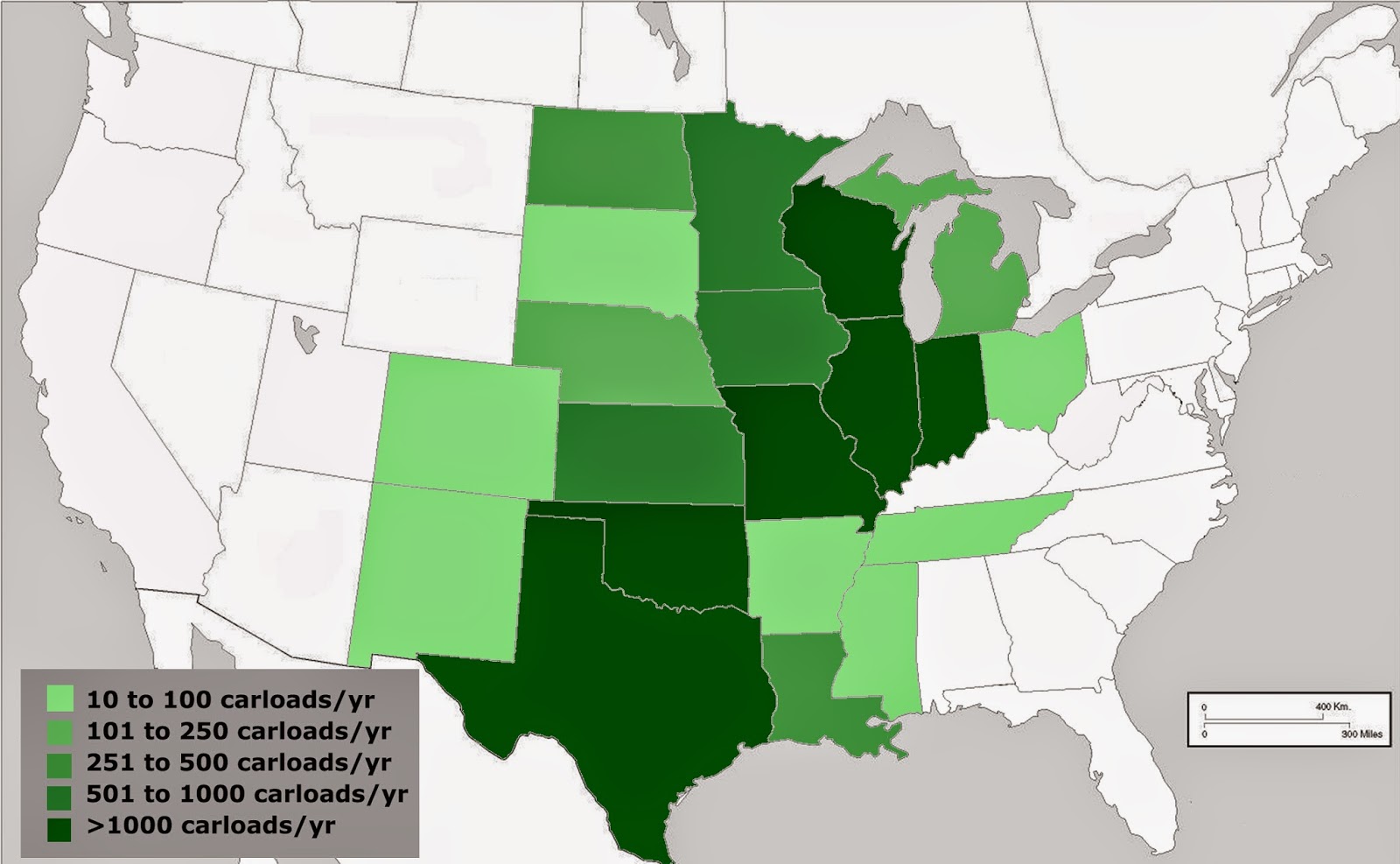

In an earlier post (http://cnwmodeling.blogspot.com/2013/12/commodity-flows-of-portland-cement.html) Brad Andonian and I looked at the commodity flow of portland cement with a focus on the eastern U.S., particularly Pennsylvania and the New York metropolitan area. We found (nationally) that the portland cement commodity flow was strong throughout the 1950s, that both special cars and ordinary general service box cars were involved, and that there was a strong regional character to the individual commodity flows. After reading this post, Andy Laurent suggested taking a look at the commodity flows of portland cement around Wisconsin. These commodity flows are important to both of our layout settings as well as intrinsically interesting [in my view ;) ], so that's what Andy and I are going to do in this post.

The Relevant Data:

The data from the 1% carload waybill survey during the 1950s (1950 through 1960 inclusive) show that Wisconsin was a net importer of portland cement. Extrapolating from the 1% sample, each year, roughly 10,000 carloads of cement entered Wisconsin, roughly 1,000 carloads of cement left Wisconsin for other states, and roughly 1,500 carloads was distributed within the state (Wisconsin - Wisconsin). The weight, distance, and revenue data for these Wisconsin shipments were not significantly different national averages.

Interestingly, the data do show a temporal (secular) variation. The period from 1950 through 1955 is strongly different that the period from 1956 through 1960. This table shows the average carloads entering Wisconsin from other states during the two time periods:

Note the decrease in the Illinois to Wisconsin traffic and the increase in the Iowa and Michigan flows to Wisconsin. The sampling error in these averages is on the order of a few tens of carloads per year. The following table shows the same information for the average number of carloads leaving Wisconsin for other states:

And finally, for traffic both originating and terminating in Wisconsin:

In the previous post I remarked that Schenker's data for the Port of Milwaukee in 1963 showed the rough equivalent of 7,500 carloads received through the Port via bulk freighter; 1,200 carloads received via car ferry from Michigan (and other points eastward); and 3 carloads shipped via car ferry to Michigan (and possibly other points eastward). These numbers are roughly consistent with the average of the 1% survey from the second half of the 1950s (if you accept the thought that a lot of the inbound bulk freighter traffic was moved out of the ports via truck rather than rail) except for the Wisconsin to Michigan flow. The 1% survey says maybe 420 carloads per year and Schenker's data says maybe 3 carloads via car ferry from Milwaukee. Is the "missing" rail traffic from Wisconsin to Michigan from the Manitowoc or Kewaunee ferries? Sent south through Chicago and around Lake Michigan? More likely, its the result of redistribution (transshipment) and that's an interesting part of the story that I think is directly relevant to Andy's setting (Green Bay). We'll revisit this topic a bit later in this post.

A Brief Tour of Selected Facilities:

In this part of the post, we look at some of the larger cement-related facilities near Lake Michigan and Lake Superior, working from Racine north to Superior (and as an added bonus, one in Duluth). Descriptive information is at the bottom of each aerial photo. The facility names are all taken from City Directories dating from 1957 through 1959. You can click on each photo to enlarge or download.

Facility Name: Consumers Co.

Location: 3 Mile Road, just north of Racine, a couple of miles inland from Lake Michigan

Date of Photo: April 9, 1955

Description: CNW's Chicago to Milwaukee double track main to west of photo (Old Line Subdivision). This is a ready-mix concrete plant. Note that this is NOT a cement manufacturing facility; it turns out there is no source of cement-quality limestone or dolomite nearby and clearly there are no kilns for cement production. Instead, aggregate is mined from the open pit and combined with cement brought in by rail (note cement silos on rail siding highlighted in blue and the two dark-colored LOs on the rail siding south of the silos). Mixed wet concrete leaves via truck. Mined aggregate also leaves via rail (note long string of hoppers on siding leading to aggregate loader.

Example Commodity Flows: Consignee for portland cement shipped from Milwaukee port terminals, originating line-haul carrier MILW, via CNW (Old Line, interchange at Jones Island or National Yard); consignee for portland cement shipped from various northern Illinois cement plants, originating line haul carrier probably CNW if shipment originated within Chicago switching district. Shipper for rock and sand to various nearby locations.

Facility Name: Huron Portland Cement Co. (bottom) and Manitowoc Portland Cement Co. (top)

Location: Port of Milwaukee, Burnham Canal

Date of Photo: April 8, 1955

Description: Cargill's Elevator E on the Milwaukee Road is to north (right) of photo. These are both marine transshipment facilities. Cement is unloaded from lake boats and stored in the tall, cylindrical silos. The cement is loaded from the silos into rail cars and trucks as needed.

Example Commodity Flows: Shipper for portland cement, originating line-haul carrier MILW.

Her sister ship, the St. Mary's Challenger made her last run in October and is being sent to Sturgeon Bay for conversion to an integrated barge/tug. Perhaps the last freight steamer on the lakes with reciprocating engines (and featured on this year's Chicago South Shore & South Bend Railroad's Christmas card!).

To be continued next post…

The Relevant Data:

The data from the 1% carload waybill survey during the 1950s (1950 through 1960 inclusive) show that Wisconsin was a net importer of portland cement. Extrapolating from the 1% sample, each year, roughly 10,000 carloads of cement entered Wisconsin, roughly 1,000 carloads of cement left Wisconsin for other states, and roughly 1,500 carloads was distributed within the state (Wisconsin - Wisconsin). The weight, distance, and revenue data for these Wisconsin shipments were not significantly different national averages.

Interestingly, the data do show a temporal (secular) variation. The period from 1950 through 1955 is strongly different that the period from 1956 through 1960. This table shows the average carloads entering Wisconsin from other states during the two time periods:

| To Wisc. | Carloads/Yr | |

| From: | <50-55> | <56-60> |

| Georgia | 0 | 20 |

| Illinois | 7083 | 3940 |

| Indiana | 683 | 40 |

| Iowa | 1783 | 2560 |

| Kansas | 50 | 120 |

| Michigan | 217 | 1160 |

| Minnesota | 783 | 780 |

| Missouri | 100 | 40 |

| Ohio | 0 | 20 |

| Oklahoma | 0 | 20 |

| Pennsylvania | 83 | 360 |

| total | 10783 | 9060 |

Note the decrease in the Illinois to Wisconsin traffic and the increase in the Iowa and Michigan flows to Wisconsin. The sampling error in these averages is on the order of a few tens of carloads per year. The following table shows the same information for the average number of carloads leaving Wisconsin for other states:

| From Wisc. | Carloads/Yr | |

| To: | <50-55> | <56-60> |

| Illinois | 0 | 80 |

| Michigan | 183 | 420 |

| Minnesota | 800 | 740 |

| Nebraska | 0 | 20 |

| North Dakota | 200 | 420 |

| total | 1183 | 1680 |

And finally, for traffic both originating and terminating in Wisconsin:

| Internal Distribution | 450 | 2520 |

In the previous post I remarked that Schenker's data for the Port of Milwaukee in 1963 showed the rough equivalent of 7,500 carloads received through the Port via bulk freighter; 1,200 carloads received via car ferry from Michigan (and other points eastward); and 3 carloads shipped via car ferry to Michigan (and possibly other points eastward). These numbers are roughly consistent with the average of the 1% survey from the second half of the 1950s (if you accept the thought that a lot of the inbound bulk freighter traffic was moved out of the ports via truck rather than rail) except for the Wisconsin to Michigan flow. The 1% survey says maybe 420 carloads per year and Schenker's data says maybe 3 carloads via car ferry from Milwaukee. Is the "missing" rail traffic from Wisconsin to Michigan from the Manitowoc or Kewaunee ferries? Sent south through Chicago and around Lake Michigan? More likely, its the result of redistribution (transshipment) and that's an interesting part of the story that I think is directly relevant to Andy's setting (Green Bay). We'll revisit this topic a bit later in this post.

A Brief Tour of Selected Facilities:

In this part of the post, we look at some of the larger cement-related facilities near Lake Michigan and Lake Superior, working from Racine north to Superior (and as an added bonus, one in Duluth). Descriptive information is at the bottom of each aerial photo. The facility names are all taken from City Directories dating from 1957 through 1959. You can click on each photo to enlarge or download.

Facility Name: Consumers Co.

Location: 3 Mile Road, just north of Racine, a couple of miles inland from Lake Michigan

Date of Photo: April 9, 1955

Description: CNW's Chicago to Milwaukee double track main to west of photo (Old Line Subdivision). This is a ready-mix concrete plant. Note that this is NOT a cement manufacturing facility; it turns out there is no source of cement-quality limestone or dolomite nearby and clearly there are no kilns for cement production. Instead, aggregate is mined from the open pit and combined with cement brought in by rail (note cement silos on rail siding highlighted in blue and the two dark-colored LOs on the rail siding south of the silos). Mixed wet concrete leaves via truck. Mined aggregate also leaves via rail (note long string of hoppers on siding leading to aggregate loader.

Example Commodity Flows: Consignee for portland cement shipped from Milwaukee port terminals, originating line-haul carrier MILW, via CNW (Old Line, interchange at Jones Island or National Yard); consignee for portland cement shipped from various northern Illinois cement plants, originating line haul carrier probably CNW if shipment originated within Chicago switching district. Shipper for rock and sand to various nearby locations.

Facility Name: Huron Portland Cement Co. (bottom) and Manitowoc Portland Cement Co. (top)

Location: Port of Milwaukee, Burnham Canal

Date of Photo: April 8, 1955

Description: Cargill's Elevator E on the Milwaukee Road is to north (right) of photo. These are both marine transshipment facilities. Cement is unloaded from lake boats and stored in the tall, cylindrical silos. The cement is loaded from the silos into rail cars and trucks as needed.

Example Commodity Flows: Shipper for portland cement, originating line-haul carrier MILW.

Facility Name: Penn-Dixie Cement Corp.

Location: Port of Milwaukee, Burnham Canal

Date of Photo: April 8, 1955

Description: This facility is across (south) of the Burnham Canal from the facilities shown above. This is another marine transshipment facility, with an adjacent warehouse for bagging cement. The facility is served by the Milwaukee Road and truck.

Example Commodity Flows: Shipper for portland cement, originating line-haul carrier MILW.

Location: Port of Milwaukee, Burnham Canal

Date of Photo: April 8, 1955

Description: This facility is across (south) of the Burnham Canal from the facilities shown above. This is another marine transshipment facility, with an adjacent warehouse for bagging cement. The facility is served by the Milwaukee Road and truck.

Example Commodity Flows: Shipper for portland cement, originating line-haul carrier MILW.

Facility Name: Universal Atlas Cement Co.

Location: Port of Milwaukee, North Menominee Canal

Date of Photo: April 8, 1955

Description: This facility is several blocks north of the Burnham Canal. This is another marine transshipment facility, with an adjacent warehouse for bagging cement. The facility is served by the Milwaukee Road and truck.

Example Commodity Flows: Shipper for portland cement, originating line-haul carrier MILW.

Location: Port of Milwaukee, North Menominee Canal

Date of Photo: April 8, 1955

Description: This facility is several blocks north of the Burnham Canal. This is another marine transshipment facility, with an adjacent warehouse for bagging cement. The facility is served by the Milwaukee Road and truck.

Example Commodity Flows: Shipper for portland cement, originating line-haul carrier MILW.

Facility Name: Kolinski Concrete Co.

Location: Port of Milwaukee, Kinnikinnic River

Date of Photo: April 8, 1955

Description: This facility is on the south side of the Kinnikinnic River near the Kinnikinnic Ave. bridge. It is just across the river from the Maple Street Ferry Dock. Note the lake boat - it is a little bit to long for any of the 1955-era cement carriers, so it was probably unloading aggregate. Both cement and aggregate are unloaded here and ready-mix cement is the primary product shipped. The Milwaukee Road's lead into the Jones Island switching area is on an elevated trestle on the left hand side of the photo. The railcar unloading facility is a dump pit that leads to a conveyor into the aggregate piles. This siding and dump pit is just to the right of the elevated trestle and connects with that track off the bottom of the photo.

Example Commodity Flows: Consignee for sand and rock, originating line-haul carrier would be any carrier in the area.

Location: Port of Milwaukee, Kinnikinnic River

Date of Photo: April 8, 1955

Description: This facility is on the south side of the Kinnikinnic River near the Kinnikinnic Ave. bridge. It is just across the river from the Maple Street Ferry Dock. Note the lake boat - it is a little bit to long for any of the 1955-era cement carriers, so it was probably unloading aggregate. Both cement and aggregate are unloaded here and ready-mix cement is the primary product shipped. The Milwaukee Road's lead into the Jones Island switching area is on an elevated trestle on the left hand side of the photo. The railcar unloading facility is a dump pit that leads to a conveyor into the aggregate piles. This siding and dump pit is just to the right of the elevated trestle and connects with that track off the bottom of the photo.

Example Commodity Flows: Consignee for sand and rock, originating line-haul carrier would be any carrier in the area.

I visited this area in 2012 and took these two photos from the bridge. The first is of the St. Marys Conquest; a post steam era cement carrier, and the second is of the facility itself:

Her sister ship, the St. Mary's Challenger made her last run in October and is being sent to Sturgeon Bay for conversion to an integrated barge/tug. Perhaps the last freight steamer on the lakes with reciprocating engines (and featured on this year's Chicago South Shore & South Bend Railroad's Christmas card!).

Facility Name: Northern Milwaukee Lime and Cement Co.

Location: Milwaukee, Silver Spring Road

Date of Photo: April 12, 1954

Description: This is a small facility on the north side of Milwaukee. The Milwaukee Road's station North Milwaukee is just to the north, where the Beer Line diverges to the east from the main. Cement was probably trucked to this location from one of the Port of Milwaukee facilities discussed above. That circular feature is not a pit mine - its an aggregate unloading area for rail cars (note the eight open-top hoppers on the loading siding). Most of the ready-mix concrete is probably shipped by truck.

Example Commodity Flows: Consignee for aggregate, originating line-haul carrier would be any local carrier.

Location: Milwaukee, Silver Spring Road

Date of Photo: April 12, 1954

Description: This is a small facility on the north side of Milwaukee. The Milwaukee Road's station North Milwaukee is just to the north, where the Beer Line diverges to the east from the main. Cement was probably trucked to this location from one of the Port of Milwaukee facilities discussed above. That circular feature is not a pit mine - its an aggregate unloading area for rail cars (note the eight open-top hoppers on the loading siding). Most of the ready-mix concrete is probably shipped by truck.

Example Commodity Flows: Consignee for aggregate, originating line-haul carrier would be any local carrier.